Memoir-ish Thoughts in Response to a Memoir

The wrenching fact: for insisting on believers' baptism, nonresistance, and separation from the state, my people were ground like wheat.

It was an odd experience for me to feel such a strong sense of kinship with Sofia Samatar while reading her book The White Mosque, as she's an author I've only recently become aware of, here writing about her father's Somali Muslim heritage, her time in Africa, and her travels in central Asia, especially considering I've never left North America. The kinship comes from our shared identity as Mennonites, which is the main topic of her book, how people across time, distance, and cultures can feel a strong sense of connection based on shared faith, ethics, and stories--and how race and ethnicity factor in for people like her, who lack a fully European lineage.

I haven't regularly attended a Mennonite church or lived in a Mennonite community since early high school, but being Mennonite was such a core part of my early identity that I'll always consider myself one on some level. I grew up in a small Kansas town with, at the time, one Methodist church and four Mennonite ones. My dad worked at the Mennonite junior college, as did an aunt and two uncles from my mom's family. Both of my grandpas led churches at some point, and my dad's dad had a career as a pastor and professor. The cousin I was always closest to is currently a professor specializing in early Mennonite history.

So when I read in The White Mosque:

Back at the hotel, I page through the history of the Great Trek: memoirs by Franz Bartsch, Herman Jantzen, Jacob Jantzen, Jacob Klaasen, and Elizabeth Unruh. Treasured photocopies of books borrowed from libraries, scanned in special collections, emailed to me by archivists in Kansas.

I thought, those are my people. So many of the names mentioned in the book--in that passage and beyond--are the ones I grew up with all around me. I don't have faces to go with the names, but the names are there, rattling around in my head, familiar with a sense of home.

And therein lies the heart of Samatar's reflections in the book: does "Mennonite" describe an ethnic heritage with a bloodline that goes back to those Dutch-German-Swiss people or does it describe a faith and belief system open to everyone of all backgrounds? The answer to both is yes, but in different, sometimes conflicting ways. That conflict is at the core of Samatar's identity, with one parent of German Mennonite background and one a converted Somalian Muslim. The Mennonite community professes to wanting her, yet there are always moments, interactions, dimensions to the identity that make her feel somewhat excluded, like she doesn't truly belong.

Despite our very European beginnings, Mennonites have always been a fairly international people. One of our core principles is separation from the state. Nationalism and patriotism are a type of idolatry, putting human institutions before God, so we keep ourselves as detached from that as circumstances allow. And we are pacifist, refusing to fight in wars. Mennonites have always been persecuted for these beliefs, and have regularly sought new nations that would allow us to reside peacefully, not drafted into national or military service.

From Samatar:

Let us recall the reason behind these struggles. The choice of Central Asia, it's true, is based on prophetic visions, but the original reason for leaving Russia is peace: the refusal of violence, even in self-defense, the refusal to enable the violence of others. In this shining absolutism lies the great honor and dignity of Anabaptist life. This is their gift to the world, and it is the reason the world needs them: these travelers are not just a quaint German-speaking cult but the stewards of a precious ethics. Back in Russia, they refused the option of forestry as a replacement for military service, because Russian foresters would become soldiers in their place.

In some ways, a people without a nation. Much fewer in number, less known and reviled, but not dissimilar to the Jewish experience. Watching Fiddler on the Roof feels familiar to me, for there were similar Mennonite communities in that part of the world at the same time. Kansas became "the breadbasket of the nation" in part due to Mennonites bringing Russian winter wheat seeds with them when they immigrated from Ukraine. My first wife was a Hmong refugee, a minority people from southeast Asia and China; when her parents asked if we understood what that was like, being a minority people living in other countries, fleeing war to new ones, we said we did. It's part of the identity.

One of the seeming contradictions in that identity is between the desire to be a people apart, as detached from worldly affairs as possible, while at the same time wanting to spread the faith through mission work. My dad spent 11 years of his childhood living in Argentina while his dad started a Mennonite seminary there. One of my uncles spent his career as the college's recruiter of international students. Others in my extended family have spent time abroad as missionaries. Many of my cousins attended the Mennonite university (as did Samatar) that includes a year studying abroad as a core experience. I never considered us "evangelical" in the way the term has always been used, sharing our beliefs not through fiery words but by demonstrating the caring, sharing empathy and love with our deeds, hoping to inspire curiosity about our motivations, but that element is there nonetheless.

Samatar's parents met and married in Somalia and she has spent some of her adulthood working in Africa. After reflecting on the Mennonite experience in Somalia, she writes:

A few conclusionsMennonites should never have interfered with Somali Muslims through their Bible classes. Having given such classes, having baptized people, they should never have left Somalia, they should have died there like Somali Christians rather than abandon the church. None of this bloodshed would have happened if not for Muslim extremists who refused to practice religious tolerance. Mennonites would never have tried to bring Somalis to Christ had they been capable of true religious tolerance. Today, Mennonites have learned religious tolerance, and work together with Muslims for peace, rather than trying to convert them. Today, Mennonites use subtler conversion techniques--for example, peace-building workshops--to infiltrate Muslim culture without getting caught. There is no point in Mennonites working with Muslims unless, eventually, they manage to bring at least one Muslim to Christ. The point of Mennonite work with Muslims is to increase understanding across religions and cultures, thereby promoting world peace. If enough Muslims became Mennonite pacifists, there would be world peace. Religious conversion of the disempowered by the powerful is a form of violence. Mennonites have done a great deal of good in Somalia, but only to themselves. Mennonites have done a great deal of good in Somalia, but only by accident.

Contradictory and paradoxical conclusions in many ways, all true at the same time. Just like Mennonite identity. Just like Samatar's identity.

In a much smaller way, like mine. My dad coached for the college, and when I was in early high school he was fired for not winning enough. I'm not sure we ever had direct, explicit conversations about it, but I know my parents felt betrayed by that decision. The college put winning ahead of community and, in effect, cast him out. He had to find a new career, and it took us too far away--a 50-minute drive; still small-town Kansas--to keep attending Mennonite churches. It was hard. Yet I also heard my parents express surprise at how welcoming non-Mennonites were, that it was easier to come in as a stranger and feel less like an outsider. We moved from an eastern Mennonite community to Kansas when I was in elementary school; and though I consider Kansas my home, I never felt my peers accepted me in the same way as they did each other. Moving away gave my family a new awareness of just how closed and exclusive Mennonite communities can be--something Samatar considers at length from the perspective of her darker skin.

Here I read of Katherine Wu, a Mennonite pastor in Taiwan, beaten unconscious in 1993 for her work with child prostitutes. I read of Salvador Alcantara, a Mennonite pastor in Colombia, threatened with death in 2003 for refusing to give up community land to paramilitary groups. And SangMin Lee, a young Mennonite in South Korea, who went to prison in 2014 for refusing military service. There is an ongoing story of Anabaptist nonviolent resistance, a mirror outside the book, all over the world. And this mirror outside the book is also outside the European Anabaptist heritage, reflecting people of color. Paradox of martyrdom: that those linked to this history by birth, but now living in comfort, feel as if the story is theirs, while others continue to live it. Paradox, that the accident of birth has come to play such a strong role in defining Anabaptism, a faith that emphasizes choice.

Yet every time I think my Mennonite identity is simply something from my past, I'm reminded it's still a fundamental part of who I am and that it will always provide me with a sense of kinship. I follow a Facebook page called "Marginal Mennonite Society," and appreciate finding those with shared values outside the community. When I traveled, long ago, to the city of Chihuahua in northern Mexico and our hosts took us to a water park in the desert, where we saw German- and Spanish-speaking Mennonites with traditional beards, bonnets, and black-and-white garb (think Amish), and were told they had notoriety in the area for the cheese they made, I felt connection and pride. And when I came across this book written by someone living in the city where I was born, teaching at the university where my dad went to graduate school, I felt compelled to read it.

Like my ruminations here in this blog post, Samatar's writing is non-linear and meandering, combining facts, events, personal stories, and meditative reflections. The skeleton of the book is the account of her experience on a bus tour of Mennonite history. In the late 1800s, Mennonites were leaving Russia to avoid being drafted into military service. One charismatic extremist convinced a group to follow him through the desert to central Asia, where they would await the end of the world. Enough survived the journey that a population settled in the area, with descendants still today--though the main settlement was destroyed by the Soviet government, who dispersed those families in the 1930s. Today, Mennonites--many of them descendants of those who moved on to America and elsewhere--go back to visit this history in group pilgrimages, touring much of Uzbekistan, through Tashkent, Samarkand, Khiva, and more.

Samatar's thoughts and observations during her trip wind through this book as its heart. The tour spurred her to do extensive, in-depth research into those original travelers, their hardships on the road, the difficulty finding a friendly place to settle, establishing their new homes as outsiders, and she includes those stories. Most of all, though, the book is about Samatar and what it means to be a Mennonite, the mingling and melding of religion, history, and culture. It's a personal exploration of her identity, and reading it nudged me into my own reflections.

One of the most powerful sections for me was when she delved into how Mennonite identity revolves around a history of persecution and martyrdom. I had forgotten that I had grown up on stories of Mennonites mistreated in Europe during the Reformation and beyond for standing up for their beliefs. Of Mennonites tarred and feathered in Kansas for refusing to fight in WWI. Of being Mennonite means getting mistreated for holding firm to unpopular beliefs. Then Samatar mentioned Dirk Willems; I didn't recognize the name, but when she told his story, I intimately knew it; when she included the etching by Jan Luyken, I immediately recognized it. This, more than any other, is the story I most associate with what it means to be Mennonite.

I think of the picture of the martyr Dirk Willems on the cover of my copy of Martyrs Mirror, that great compendium of Anabaptist stories. The image shows an icy river and two men. One man has fallen through the ice; the other reaches down to save him. Most of the images in Martyrs Mirror show scourged or dying martyrs, but in this picture Willems is not suffering. It's the man chasing him, the man paid to capture him, the thief catcher, who has plunged into the deadly water. And Willems, who might have escaped, has turned back, his hands outstretched, he's going to rescue this man, his enemy, his neighbor, his brother. He saved the thief catcher's life. And he was caught. And he was burned at the stake on a windy day outside the town of Leerdam.It's hard to express the power of this story, its centrality. It's the only story in Martyrs Mirror I don't remember learning. As if I've always known it. Is there a genetics of storytelling? Which is closer to me: this story or the shape of my hand?All the accounts in Martyrs Mirror tell of suffering and dying for one's faith, but the Dirk Willems story adds something more: a life. A life that was saved. In giving his own life to save his persecutor, Willems becomes a mirror of Christ.In his critique of the leading role martyr histories play in Mennonite consciousness, the writer Ross Bender argues, "The Mennonite story is not a narrative but a sort of consensual hallucination." I ask myself, What else could it be? What is any group identity but a story a whole community has swallowed?

Later, she concludes the section:

The coziness of it. Martyrology as comfort food. The history that nourished the Ak Metchet Mennonites warms me just as well. Bitter in the belly, it tastes like honey in the mouth. Harrowing, heartrending, brutal, the story is home.

To this day, after attending other churches, getting a seminary degree from other denominations, I still can't conceive of Christian belief that isn't based on this idea. Christianity means love for others to the extent that you'd rather be killed than kill, save your enemies at the cost of your own life. I may not be actively Mennonite, but this is still, as Samatar says, home.

Yet that's an easy thing for me to feel, to say, because I am white. I come from European stock, have the Kansas Mennonite lineage. One of my seminary professors, when I told her I used to be a Mennonite, said, "Once a Mennonite, always a Mennonite." Would she say the same to Samatar, though?

I understand that someone like my father, deeply influenced by the Mennonite story, had no place in it once he was no longer a practicing Mennonite, unlike other nonpracticing Mennonites who carry the banner of blood. But experience, just like blood, endures. How I wish this could be recognized, acknowledged, and celebrated, stories granted a status equal to that of DNA, perhaps even greater! It's the days spent together that make us part of each other. There is a genetics of storytelling, for stories too are encoded, inherited, lodged in the flesh.

And that's what her book is really about. It includes fascinating history, describes a trip that sounds wonderful, shares facts about the author's life. But really it's an exploration of identity, of Samatar herself, moreso how she represents an experience of an identity that is both inclusive and exclusive at the same time. An identity that has transcended place and people. And, through this book, Samatar calls us make the transcendence greater, resolve the contradiction in favor of inclusivity, and make "Mennonite" something more open to all.

I truly appreciate it. And I think other readers will, too.

Here are some other things I've recently read and thought.

Memes:

In his later years, he added a new apex to the pyramid: self-transcendence. . . .Although engineering our way out of trouble is possible, it can’t happen until we transcend ourselves, seeing beyond our own individual well-being to the needs of us all.This is what the final stage of Maslow’s pyramid is about: Having met our basic needs at the bottom of the pyramid, having worked on our emotional needs in its middle and worked at achieving our potential, Maslow felt we needed to transcend thoughts of ourselves as islands. We had to see ourselves as part of the broader universe to develop the common priorities that can allow humankind to survive as a species.

Once you meet all of your personal needs, you can see beyond yourself and realize how interconnected you are with everyone and everything else.

Hmm. Hrm.

Well, considering I fundamentally agree with this statement by Patton Oswalt from his book Zombie Spaceship Wasteland: "I want to experience as many different tastes, sights, emotions, conflicts, and cultures as possible, so that I can expand the canvas of my memory and enrich my comedy [life]." . . .

Yet I also believe life is too unpredictable, ephemeral, and transitive for long-term expectations, that it's more about taking things as they come and setting a trajectory with guiding intentions than trying to have set, specific plans that are likely as not to be stymied; it's best to live in the moment and focus more on your orientation than events. . . .

And I'm basically a lazy, gluttonous person unwilling to suffer short-term inconvenience for long-term gains like saving money to pay for a major trip or staying in shape enough to climb the mountains I want with my kids. . . .

Considering all of that, I try to keep myself open to adventure and experiences, seize the ones I can, but can't really wrap my head around the idea of an explicit list of bucket items.

Though some things from the past I can check off:

- Hiked Pike's Peak twice (plus many others)

- Competed in a national championship sporting event (cross country NCAA division II with Emporia State, and I had the worst race of my career)

- A bilingual wedding with pastors from two churches (my first wife, of 15 years, was Hmong, part of a local refugee community)

- A trip to Mexico on a Mexican bus line where I was the only person who didn't speak Spanish, staying for a week on the couch of friends

- Having children (which didn't happen until my second marriage)

- A lifetime of interesting experiences, road trips, cheap cruises, losses and heartbreak, growth . . . and there's still so much left unexperienced.

A story of legend and myth come to life in a fairy tale forest, where animals talk and mushrooms can do the most fantastical things. Dense and wordy, clever and witty, and, most of all, full of character and heart. It's a story about identity and division, ingrained fear and hatred. It's a quest to the land of the dead full of encounters with monsters and a myriad of strange creatures. It's a cross-cultural immersion experience. It is delightful.

One of Osmo's assigned companions is astoundingly cantankerous:

But no one listens to Bonk the Cross on account of how I am rude and they don't like me. But I enjoy being rude more than I enjoy company, so they can stuff it. You, young sir, are clearly part monkey and part otter, and while, yes, 'motters' are rare, they're hardly anything to throw a party about. Believe me! I am really and truly never ever wrong, ask anybody. If I am wrong, it's only that I'm wrong just now. Wait a bit, and you'll see I'm right in the end. And if I'm still wrong, you just haven't waited long enough, so give it another few years. . . .Every day is a game, and as long as someone else is unhappier than me by close of business, Bonk the Cross wins!

The other is a determined isolationist:

"Do you know," she said between hics, "pangolins don't even have any numbers other than one in our language! One is the best number. The only correct number. A pangolin does not count one, two, three, four, five, six, a hundred. A pangolin counts one, awkward, unpleasant, disturbing, dreadful, suffocating, completely intolerable. Guest is an extremely naughty word. Company is worse than that."

For a taste. Valente is an inventive and wonderful storyteller.

"As challenger and guest, you may choose your weapons. I can summon a trolley from the storeroom with anything you like. What's it to be? Swords? Crossbows? Trebuchets? Nunchucks? How about a nice musket? Oooh, or blow darts!""Feelings," Bonk said simply. He put his pays behind his back and rocked up and down on his feet, powerfully proud of himself."Feelings? But that's not a weapon.""Then you're not doing 'em right."

About the same time I was reading that, I came across this.

There's overlap in how the brain processes physical and emotional pain.Words in the semantic session associated with social pain led to increased activity in many of the same areas found for physical pain. The researchers concluded that their results confirm that "semantic pain partly shares the neural substrates of nociceptive pain." . . .The most important takeaway for me is that this is another example of research clearly demonstrating the fallacy of separating the brain from the body. Humans, like all animals, are integrated, holistic beings. We can easily see a broken bone and infer the real extreme pain that the person must be experiencing. It's critical to realize that the injuries and pain that a person might have from social experiences are also real.That old expression, often used to put down feelings, is apt—but for a different reason. It really is "all in your head," but so is the entire universe. All of our experiences, regardless of point of origin, are in our heads. That's the point of being conscious.It doesn't matter whether our brains get information from our skin, our ears, our eyes, or our thoughts; hurtful intentions can cause pain. While my mom wasn't completely correct in using that old saying, her intentions were always helpful and did help manage hurt.

Pain is pain. Feelings can be weapons.

Our brains respond to justifications for prejudiceIf social norms appear to justify violence against a group, a whole lot of latent prejudice is going to come out of the woodwork at once. Jay Van Bavel, a professor of psychology and neural science at NYU, put it succinctly:Genuine prejudices are often restrained by values and norms, until the situation allows people to justify their expression. …This is why it's crucial not to openly justify or rationalize violence against other groups. People who were (secretly) prejudiced all long will see this as a justification to express their own virulent beliefs, which can lead to mass discrimination or violence.Van Bavel referenced another study which found that social norms were strong predictors of individuals’ expressions of prejudice. In that work, the people who worked hard to suppress their own prejudices were the most influenced by social norms, and would express strong prejudice when it seemed socially acceptable.Is this Justification-Suppression Model view of the world depressing? Perhaps, in that it says that there are massive aquifers of prejudice bubbling just below our collective surface. But I find it hopeful. It suggests that effort matters, and practice matters, and individual values matter, and that social norms can prevent prejudicial behavior, even when prejudice is common.Like it or not, social media influences social norms. So if you do choose to post on social media, or to share a post, stop to think about the larger narrative it enforces. Hopefully, the narrative is that the harming of innocents is always a tragedy to be mourned, no matter who those innocents are.

Don't be a maker of propaganda.

by Muon Thi Van, ill. by Miki SatoBut from any side,it looks like a circle.We live on this side,on a hillshaped like a triangle.The shape of our dooris a rectangle.The shape of our tableis a square.The shape of this wateris a cup,but sometimes it's a cubeor a cloud.The shape of lightis all the colors of the sunset --red, yellow, blue,tangerine, chartreuse, mulberry, too.The shape of orderis numbers --ones you can count up to,and ones you can't.The shape of thinkingis quiet.The shape of learningis a question.The shape of surpriseis best when it hideswhat's inside.is a scarf flapping.The shape of friendshipis a dog.The shape of warmthis a space waiting to be filled.The shape of a good storywraps around tight.Some shapes change.But some remain the same.The shape of my fingerswill always fit yours.And the shape of my lovewill always be you.

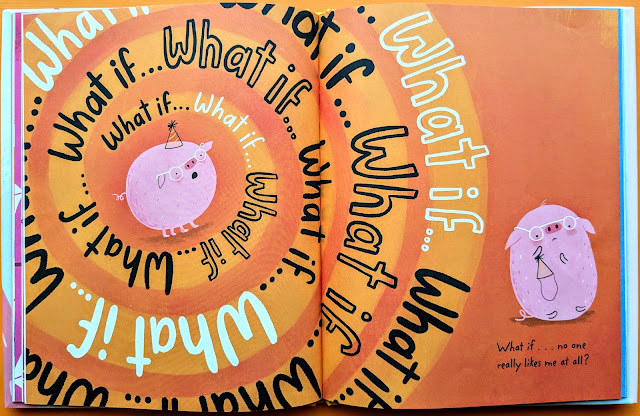

The shape of learning is a question.

Related: recently I started Moby-Dick on audiobook to see if the semi-intelligible droning would help my nine-year-old drift into sleep, and was tickled by this thought from the first paragraph:

Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off—then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can.

I, too, sometimes feel like randomly attacking everyone I see.

To keep with the memoir-ish theme, I really enjoyed reading The He-Man Effect: How American Toymakers Sold You Your Childhood by Brian "Box" Brown. My review:

He-Man was my high school swim team's mascot. Not officially, and not in

any way that really concerned me. I don't even know the story; I just

know that some of the guys a year or two older than me had a little

He-Man figure they took to all of our meets to joke around with. It was

entirely ironic, meant to be silly. But He-Man was always there.

Which doesn't really have anything to do with the book, except to say the heart of this book is about the children's toys and TV of the 1980s (He-Man, G.I. Joe, and the Transformers, in particular), which is me. I graduated high school in '89, watched the media discussed in this book, had some of the toys (still have a few of them in boxes), grew up on it. I read it thinking, this is my life.

But more than a book about toys and TV, this is implicitly a book about stories. About the power of stories. Humans only understand the world via stories. We tell ourselves stories about who are, what we've done, and what we hope to do. We tell others stories to define our groups, both in-groups and out-groups. Stories unite and divide us. They define us socially and individually. They are a core feature of the human condition.

In this book, Brown delves into the ways entertainment corporations and toy companies have allied to use stories to capture interest in their products. How TV, movies, and other forms of storytelling have basically functioned as advertising for toys. By tapping into young imaginations, eager and impressionable and not yet fortified against manipulation, and giving them the stories they should play out, which require the merchandise the companies sell. And using the nostalgia of adults to maintain a cycle that perpetuates.

At first I thought this might be a simple, uninformative primer on basic media literacy, but Brown's depth of research and detail is impressive. After mentioning Julius Caesar's early use of propaganda and a bit of history, his story really starts with the posters of the first World War. And how some of the minds behind that propaganda moved into the business world after. Then the creation of Mickey Mouse and the emergence of Disney:

We're always going to define ourselves through stories. Should we pay more attention to who controls them?

Which doesn't really have anything to do with the book, except to say the heart of this book is about the children's toys and TV of the 1980s (He-Man, G.I. Joe, and the Transformers, in particular), which is me. I graduated high school in '89, watched the media discussed in this book, had some of the toys (still have a few of them in boxes), grew up on it. I read it thinking, this is my life.

But more than a book about toys and TV, this is implicitly a book about stories. About the power of stories. Humans only understand the world via stories. We tell ourselves stories about who are, what we've done, and what we hope to do. We tell others stories to define our groups, both in-groups and out-groups. Stories unite and divide us. They define us socially and individually. They are a core feature of the human condition.

In this book, Brown delves into the ways entertainment corporations and toy companies have allied to use stories to capture interest in their products. How TV, movies, and other forms of storytelling have basically functioned as advertising for toys. By tapping into young imaginations, eager and impressionable and not yet fortified against manipulation, and giving them the stories they should play out, which require the merchandise the companies sell. And using the nostalgia of adults to maintain a cycle that perpetuates.

At first I thought this might be a simple, uninformative primer on basic media literacy, but Brown's depth of research and detail is impressive. After mentioning Julius Caesar's early use of propaganda and a bit of history, his story really starts with the posters of the first World War. And how some of the minds behind that propaganda moved into the business world after. Then the creation of Mickey Mouse and the emergence of Disney:

Humans attach emotion to everything we do. Our emotions are not separate from our thoughts. Particularly emotional childhood experiences affect our behavior in ways we're not necessarily even conscious of. The memories and emotions stay with us. They shape our identity. What Disney had stumbled onto (or figured out), is that they could tie these emotional experiences that shape our identities to their media property.He mentions Citizen Kane, that the key to the movie is Kane's yearning nostalgia for the emotions of childhood. He charts the development of animated TV shows and product tie-ins, resistance in the 70s, then the erasure of regulations in the 80s that opened the door to shows explicitly created for the purpose of selling toys. That has been the norm since. Brown focuses particular attention on the 80s not only because that's when the model was perfected, but because . . .

The 80s cartoon toy boom ended up being a unique moment in time. A generation of kids were all engrossed in the same media. They were the first generation to experience this kind of acute advertising with total abandon.Since then, the amount of media, thanks to cable and the Internet, has exploded and diversified, with the stories being much less monocultural than before. Though now, of course, Disney is Star Wars, and people my age can't stop watching with our families.

At some point we deemed a child's imagination too precious to be subject to the power we discovered in propaganda and advertising. Then, in the face of the ever quickening pace of technology, these boundaries were removed. Corporations are being granted more and more space in our brains, influencing us in ways we're not even aware of. We can't know how this will affect the next generation. But corporations are already banking on their future nostalgia. Today's media corporations have a power over us that is unprecedented on planet Earth and always growing. Their goal is clear. It's the same goal of all capitalist enterprises: cradle to grave brand loyalty.That's a quick summary. Brown gets into the specifics of the people involved, what they did and said, how all of the strategies were intentionally developed. He supports all of his claims.

We're always going to define ourselves through stories. Should we pay more attention to who controls them?

Alison Baileyto write a poemfirstit must survive a kindergarten schoolyard trauma, a sunburn on an overcast day,bury, in a small paper box that once held a bar of soap,the thumbnail-sized frog that was once a polliwog it caught at Mrs. Anderson’spond whose tail fell off and hind legs emerged like quotation marks & hadbeen kept in the rinsed Best Foods mayonnaise jarmust worry a tobacco-stained grandfather’s handrun over a jackrabbit on I-40 in the Arizona desertget divorcedburn dinnerconfess its sinssuffer food poisoningrefuse to eat blue M&M’shang, on a sweet-breezy July, laundry in Fishtail, Montana—eye the distant SawtoothMountains & hum “Waltzing Matilda” which it learned from Miss Vineyardin second grademust fear thunderrush to focus its binoculars on the wintering Lazuli Buntingtell white lies to be kindshout “Heavens to Betsy!”be part of a standing ovationendure recurring nightmaresquestion the crossing guard about the origin of “fingers crossed”develop calluses as it learns to play the twelve-string banjohave its hair smell of campfire smokeswat, during a humid-summer dusk, at mosquitoes on a dock full of splinteredcypress wood at Half Moon Lake in Eau Claire, Wisconsinforever dislike Brussels sprouts because it overcooked them and they smelled likerotten eggsmust watch windweep at a funerallose anythingimagine infinitydoubt God’s existencedie a little every daythen, perhaps——from Ekphrastic ChallengeSeptember 2023, Artist’s Choice

And this might just be the best thing I've ever gotten out of Inspirobot, not funny or twisted or cliche or random nonsense, but actual, poignant wisdom.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home